Or you can get OmniFocus for iOS, Mac, and web for just one price with the OmniFocus Subscription. Download the app for details. Use OmniFocus to accomplish more every day. Create projects and tasks, organize them with tags, focus on what you can do right now — and get stuff done. Omnifocus for mac 3 0. “OmniFocus 3 for Mac is a powerful and highly-refined task manager; the culmination of ten years of development. It’s the app that I trust for honouring my commitments, making effective use of my time and energy, and giving all areas of my life the appropriate amount of attention.”. OmniFocus 3 for Mac Released by Brent Simmons on September 23, 2018. OmniFocus 3 for Mac is now shipping! It’s free to download, and it offers a two-week free trial. Read all about it on the OmniFocus 3 for Mac product page. From there you can download it directly or go to the Mac App Store and download it there.

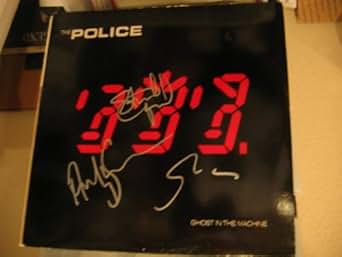

Buy 'Ghost In The Machine by The Police' MP3 download online from 7digital United States - Over 30 million high quality tracks in our store. The Police needed a rest, took it and 'Ghost In The Machine' is the result, a tougher record than ever before, songs frequently pared to one unrelenting riff, early reggae flavours retained, but tainted by an extra touch of funk, an additional dollop of rock'n'roll.

The 'ghost in the machine' is British philosopher Gilbert Ryle's description of René Descartes' mind-body dualism. Ryle introduced the phrase in The Concept of Mind (1949)[1] to highlight the view of Descartes and others that mental and physical activity occur simultaneously but separately.[2]

Gilbert Ryle[edit]

Gilbert Ryle (1900–76) was a philosopher who lectured at Oxford and made important contributions to the philosophy of mind and to 'ordinary language philosophy'. His most important writings include Philosophical Arguments (1945), The Concept of Mind (1949), Dilemmas (1954), Plato's Progress (1966), and On Thinking (1979).

Ryle's The Concept of Mind (1949) critiques the notion that the mind is distinct from the body and refers to the idea as 'the ghost in the machine'. According to Ryle, the classical theory of mind, or 'Cartesian rationalism', makes a basic category mistake, because it attempts to analyze the relation between 'mind' and 'body' as if they were terms of the same logical category. This confusion of logical categories may be seen in other theories of the relation between mind and matter. For example, the idealist theory of mind makes a basic category mistake by attempting to reduce physical reality to the same status as mental reality, while the materialist theory of mind makes a basic category mistake by attempting to reduce mental reality to the same status as physical reality.[3][4]

The Concept of Mind[edit]

Official doctrine[edit]

Ryle states that (as of the time of his writing, in 1949) there was an 'official doctrine,' which he refers to as a dogma, of philosophers, the doctrine of body/mind dualism:

There is a doctrine about the nature and place of the mind which is prevalent among theorists, to which most philosophers, psychologists and religious teachers subscribe with minor reservations. Although they admit certain theoretical difficulties in it, they tend to assume that these can be overcome without serious modifications being made to the architecture of the theory.. [the doctrine states that] with the doubtful exceptions of the mentally-incompetent and infants-in-arms, every human being has both a body and a mind. .. The body and the mind are ordinarily harnessed together, but after the death of the body the mind may continue to exist and function.[5]

Ryle states that the central principles of the doctrine are unsound and conflict with the entire body of what we know about the mind. Of the doctrine, he says 'According to the official doctrine each person has direct and unchangeable cognisance. In consciousness, self-consciousness and introspection, he is directly and authentically apprised of the present states of operation of the mind.[6]

Ryle's estimation of the official doctrine[edit]

Ryle's philosophical arguments in his essay 'Descartes' Myth' lay out his notion of the mistaken foundations of mind-body dualism conceptions, suggesting that to speak of mind and body as substances, as a dualist does, is to commit a category mistake. Ryle writes:[1]

Such in outline is the official theory. I shall often speak of it, with deliberate abusiveness, as 'the dogma of the Ghost in the Machine.' I hope to prove that it is entirely false, and false not in detail but in principle. It is not merely an assemblage of particular mistakes. It is one big mistake and a mistake of a special kind. It is, namely, a category mistake.

Ryle then attempts to show that the 'official doctrine' of mind/body dualism is false by asserting that it confuses two logical-types, or categories, as being compatible. Mac menu bar cleaner free. He states 'it represents the facts of mental life as if they belonged to one logical type/category, when they actually belong to another. The dogma is therefore a philosopher's myth.'

Arthur Koestler brought Ryle's concept to wider attention in his 1967 book The Ghost in the Machine.[7] The book's main focus is mankind's movement towards self-destruction, particularly in the nuclear arms arena. It is particularly critical of B. F. Skinner's behaviourist theory. One of the book's central concepts is that as the human brain has grown, it has built upon earlier, more primitive brain structures, and that this is the 'ghost in the machine' of the title. Koestler's theory is that at times these structures can overpower higher logical functions, and are responsible for hate, anger and other such destructive impulses.

Popular culture[edit]

- Author Stephen King used the concept of the ghost in the machine to refer to his character Blaine the Mono, the train with a split mind that runs the town of Lud in his 1991 novel The Dark Tower III: The Waste Lands from his series The Dark Tower.

- Arthur C. Clarke's novel 2010: Odyssey Two contains a chapter called 'Ghost in the Machine', referring to the virtual consciousness inside a computer.

- The Japanese manga and anime Ghost in the Shell takes place in a future where computer technology has evolved to be able to interface with the human brain making artificial intelligence and cyber-brains indistinguishable from organic brains. The main character, Major Motoko Kusanagi has a body that is completely cybernetic, her brain being the only part of her that is still human. The manga's creator Masamune Shirow adapted the title from the 1967 Arthur Koestler book The Ghost in the Machine.

- A Season 3 episode of The Transformers (TV series) (1986) is titled 'Ghost In The Machine', where the ghost of Starscream possesses Scourge, Astrotrain, and Trypticon in a scheme to get Unicron to recreate his body. In this case it is a literal ghost in literal machines (robots).

- Dr. Alfred Lanning, a central character of I, Robot, uses the phrase 'ghosts in the machine' to refer to the process of artificial intelligence unexpectedly evolving past its original intended purpose.

See also[edit]

- Mind (The Culture) - Iain M. Banks 'Culture' series

References[edit]

- ^ abRyle, Gilbert, 'Descartes' Myth,' in The Concept of Mind, Hutchinson, London, 1949

- ^Tanney, Julia 'Gilbert Ryle', in Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy; Dec 18, 2007; substantive revision Mon Nov 2, 2009 (accessed Oct. 30, 2012)

- ^de Morais Ribeiro, Henrique, 'On the Philosophy of Cognitive Science', Proceedings of the 20th World Congress of Philosophy, Boston MA, 10–15 August 1998 (accessed 29 October 2012)

- ^Jones, Roger (2008)'Philosophy of Mind, Introduction to Philosophy since the Enlightenment', philosopher.org (accessed Oct. 30, 2012)

- ^Ryle, Gilbert,The Concept of Mind (1949); The University of Chicago Press edition, Chicago, 2002, p 11

- ^Cottingham, John,Western philosophy: an anthologyGoogle Books Link

- ^Koestler, Arthur, The Ghost in the Machine, (1967)

Sources[edit]

- Koestler, Arthur (1990-06-05) [1967]. The Ghost in the Machine (1990 reprint ed.). Penguin Group. ISBN0-14-019192-5.

- Ryle, Gilbert (2000-12-15) [1949]. 'Descartes' Myth'. The Concept of Mind (New Univer ed.). University of Chicago Press. ISBN0-226-73296-7.